Managing Anxiety and Stress in Students: A Health Professional’s Perspective

🕒 Read time: 10 mins

By Caren Smith* - School Nurse

Setting the Scene

Walking away from the ward for the last time, the familiar smell of disinfectant and the beeping of machines gradually faded; this marked the end of a significant chapter in my life. I felt both nervous and excited. As a staff nurse, my work had been challenging yet rewarding, but it was time to embark on my next adventure as a school nurse.

Almost immediately, I sensed that I had found my true calling. I have the privilege of nurturing the health and well-being of students, focusing on their overall wellness rather than just physical health. Each day, I witness the amazing potential in these young individuals, which motivates me to help them succeed.

In recent years, I have observed a remarkable rise in anxiety and stress among young people. This is often exacerbated by the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, academic pressures, and social dynamics. One moment stands out in my memory: a student arrived at the medical centre visibly shaking after receiving a poor grade on an exam. As we spoke, I realised this was more than just a single setback; it was rooted in the fear of letting parents down and feeling inferior to peers. Moments like these remind me of the importance of being a supportive presence in their lives.

I frequently assist students in coping with daily stressors, whether it involves calming a child overwhelmed by social dynamics or helping another grapple with the pressure of upcoming college applications. It is all about connection and care. I strive to create resilience and well-being among students, turning adversity into opportunity through positive interactions and supportive conversations. I love that each day is different, consoling a student over a breakup one moment and cheering another on as they open up about their problems the next, reminding me that emotional well-being is just as crucial as physical health.

In my upcoming insights, I will explore how anxiety and stress affect young people, examine the daily stressors they encounter, and explain the physiological responses in our bodies. I will also provide helpful resources and evidence-based strategies for managing stress within the school environment, all aimed at enhancing our understanding of and support for the mental well-being of young people.

The Rising Tide of Anxiety and Stress

Recent data from NHS Digital (2023) highlight a concerning trend: the prevalence of probable mental disorders among children has increased significantly since the pandemic, affecting approximately one in five children aged 8–16.

Anxiety is now one of the most common reasons for referrals to mental health services, with numbers more than doubling compared with pre-pandemic levels. Many students have struggled to readjust to in-person learning. Social reintegration, loss of confidence, and renewed academic pressures have compounded existing stress, making schools vital settings for early identification and intervention.

Emerging research shows that anxiety and other mental health difficulties are strongly associated with increased school absenteeism, as children experiencing elevated levels of anxiety are significantly more likely to avoid or miss school, leading to a reinforcing cycle of academic decline and emotional distress (Finning et al., 2019).

Understanding Common Stressors

1. Academic Pressures

Academic pressure is one of the most common forms of stress among students. Anxiety interferes with working memory and cognitive performance, especially in exam situations (Ng & Lee, 2010; Almarzouki, 2023).

Working memory is vital for processing, storing, and manipulating information. Chronic stress disrupts the functioning of the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, essential areas of the brain that support learning and memory (McEwen, 2017).

A side effect of chronic stress is poor concentration and slow recall, exacerbating the cycle of anxiety and disappointment. This aligns with processing efficiency theory, which proposes that anxious individuals exert greater mental effort to sustain performance, often at the cost of efficiency (Ng & Lee, 2010).

2. Social Pressures

Social comparison, peer pressure, and the overwhelming presence of social media can significantly increase stress levels. Today’s youth are expected to cope with cultural spaces in which a person’s worth is often decided by their online presence, creating unrealistic ideals of success and beauty.

3. Family Expectations

Parents’ expectations can also add to student stress. While encouragement can be motivating, excessive pressure may lead to burnout and emotional distress. Supportive communication, along with realistic expectations, is key to sustainable outcomes.

The Physiology of Stress

When faced with stress, the body’s sympathetic nervous system activates the “fight-or-flight” response, releasing cortisol and adrenaline. While this is adaptive in the short term, prolonged activation can impair concentration, sleep, and emotional regulation (Lupien et al., 2018).

Sustained high cortisol levels can damage neurons in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, reducing working memory capacity and overall cognitive performance (Almarzouki, 2023). Academic functioning and well-being are, therefore, deeply connected.

Evidence-Based Coping Strategies

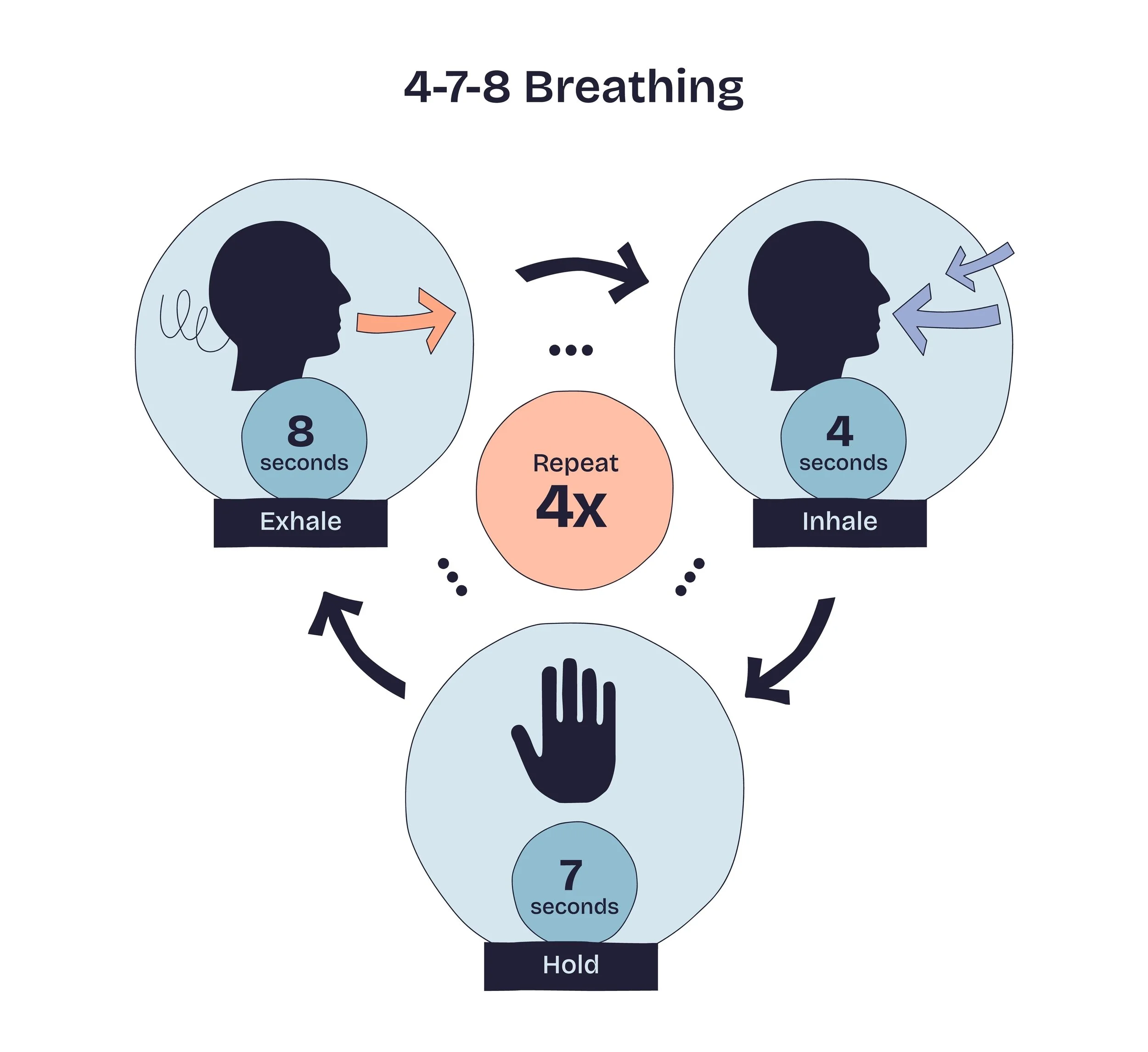

1. Breathing Practices for Stress and Anxiety

Controlled breathing has numerous positive effects on reducing anxiety and stress. A systematic review by Bentley et al. (2023) outlines the benefits of breathing exercises on emotional regulation and resilience.

The 4-7-8 method, inhale for four seconds, hold for seven, and exhale for eight, is a particularly effective approach. These strategies are simple enough to incorporate into daily school routines, preparing students for high-pressure situations. Integrating such exercises into school well-being programmes provides students with lifelong tools for emotional regulation.

2. Mindfulness

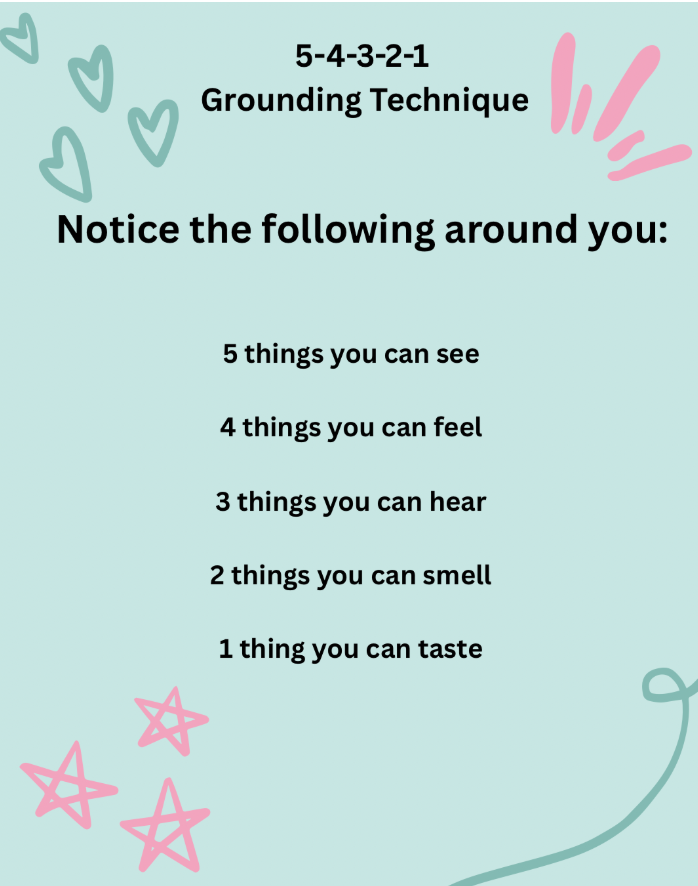

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have been shown to reduce anxiety and stress in young people, enhancing awareness, emotional regulation, and coping skills (Dunning et al., 2019). In my experience, helping pupils focus on the present moment supports them during episodes of acute anxiety and stress.

3. Gratitude Journaling

Encouraging students to keep a gratitude journal and noting three positive reflections daily, has been shown to improve sleep quality and emotional resilience (Bono et al.,2020)

4. Creating Supportive Spaces: The Sensory Area

A designated sensory area in schools can provide a calm, safe space for students to self-regulate.

Features include:

Fidget toys and tactile objects for grounding

Weighted blankets for comfort and security

A darkened, quiet zone for sensory relief

Allowing brief sensory breaks can prevent escalation into panic or emotional overload.

5. Consistency, Listening, and Building Trust

The behaviours we see in young people are often just the visible “tip of the iceberg.” To provide meaningful support, we must look beneath the surface.

Consistent support, active listening, and taking time to check in create trust and connection. Whether a student needs help managing friendships, academic struggles, or emotional issues, knowing there is a reliable adult available can help reduce anxiety. Over time, this consistency encourages students to seek help rather than withdraw.

6. School-Based Mental Health Interventions

Whole-school approaches such as peer support groups encourage empathy and openness.

Older students who have managed similar challenges can become relatable role models for younger students, helping to normalise the process of seeking support. For older pupils, mentoring offers an opportunity to reflect on their experiences while developing leadership and communication skills. This model of reciprocity nurtures a culture that values mental health.

7. Professional Support

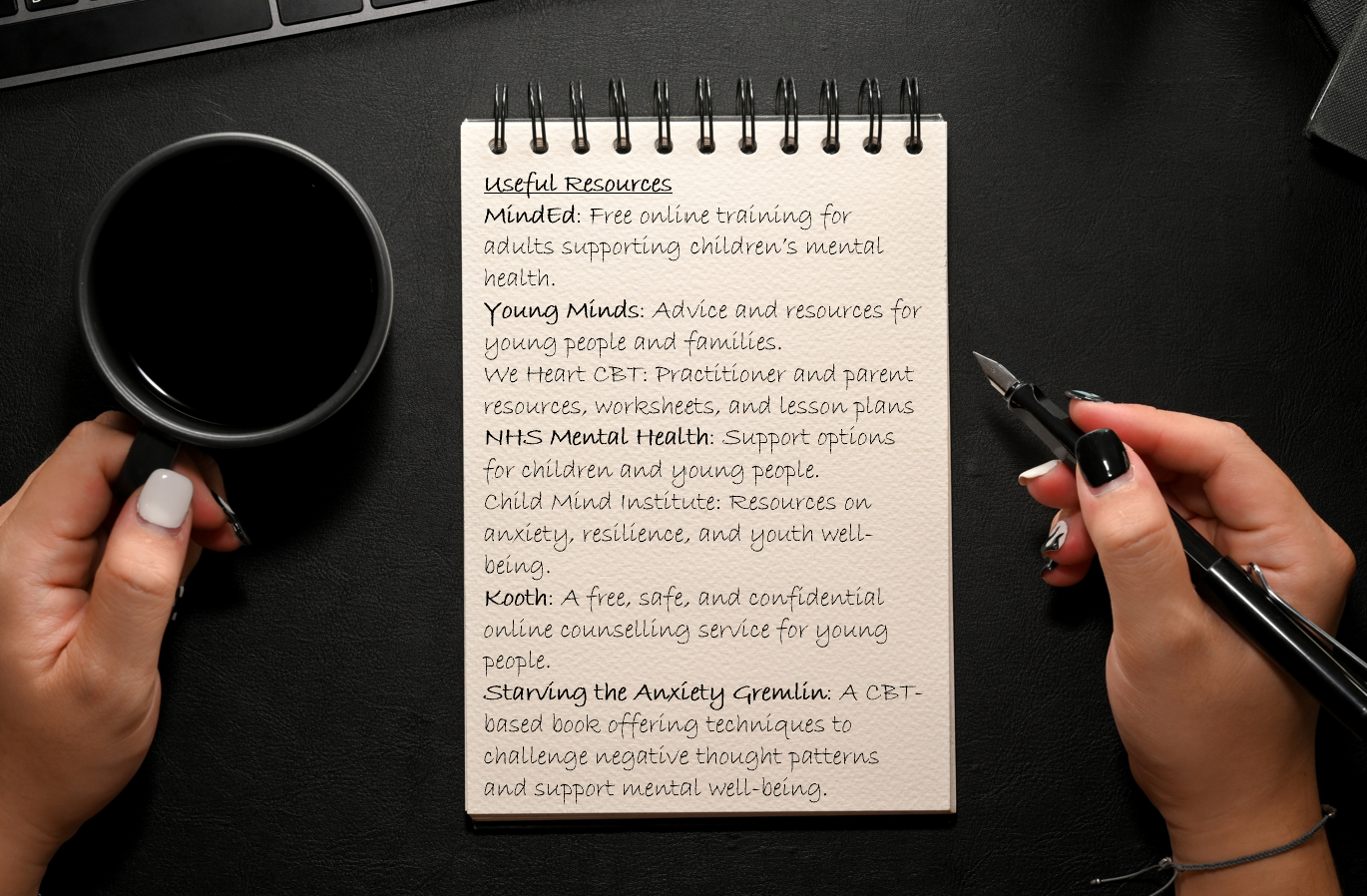

For students with persistent or severe anxiety, early intervention is essential. Collaboration with GPs, school counsellors, and Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) ensures prompt access to therapy and specialist care.

8. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

CBT helps young people understand their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours, enabling positive changes in thinking patterns. CBT is recommended as an initial treatment option for children and young people (aged 5–18) with mild to moderate symptoms of anxiety or low mood (NICE, 2023).

Staying Positive and Reinforcing Strengths

Supporting students with anxiety and stress requires a compassionate, strengths-based approach. Reinforcing courage and progress and praising the bravery it takes to acknowledge difficult feelings, builds confidence and resilience (Rudland, Golding & Wilkinson, 2020).

A high-achieving student with social anxiety gradually began to open up during our sessions. By creating a safe, supportive environment, we collaborated with teachers and parents to address her triggers. Adjusting classroom lighting and improving her sleep routine significantly reduced her anxiety. Introducing the 4-7-8 breathing technique during moments of acute stress further supported her self-regulation. Over time, her confidence grew, and she concluded our sessions with greater self-awareness and resilience.

References

Almarzouki, A.F. (2023) The relationship between stress, working memory, and academic performance: A neuroscience perspective. King Abdulaziz University, Department of Clinical Physiology, Division of Neuroscience.

Bentley, T.G.K., D’Andrea-Penna, G., Rakic, M., Arce, N., LaFaille, M., Berman, R., Cooley, K. and Sprimont, P. (2023) ‘Breathing practices for stress and anxiety reduction: Conceptual framework of implementation guidelines based on a systematic review of the published literature’, Brain Sciences, 13(12), pp. 1612–1612. PMCID: PMC10741869. PMID: 38137060.

Bono, G., Mangan, S., Fauteux, M. and Sender, J. (2020) ‘A new approach to gratitude interventions in high schools that supports student wellbeing’, The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(5), pp. 657–665. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1789712.

Child Mind Institute (2025) About us: A global nonprofit working to transform children’s mental health. Available at: https://childmind.org/about-us/ (Accessed: 6 November 2025).

Collins-Donnelly, K. (2013) Starving the Anxiety Gremlin: A Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Workbook on Anxiety Management for Young People. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Dunning, D.L., Griffiths, K., Kuyken, W., Crane, C., Foulkes, L., Parker, J. and Dalgleish, T. (2019) ‘The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(3), pp. 244–258. PMCID: PMC6546608.

Finning, K., Ford, T., Moore, D.A. and Ukoumunne, O.C. (2019) ‘Emotional disorder and absence from school: Findings from the 2004 British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey’, European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(4), pp. 471–479. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1218-5.

Kooth (2025) Whatever you are feeling, we’re here to help. Available at: https://www.kooth.com (Accessed: 6 November 2025).

Lupien, S.J., McEwen, B.S., Gunnar, M.R. and Heim, C. (2018) ‘Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour, and cognition’, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 19(10), pp. 578–590.

McEwen, B.S. (2017) ‘Neurobiological and systemic effects of chronic stress’, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 18(6), pp. 439–450.

MHFA England (2025) Youth Mental Health First Aid. Available at: https://mhfaengland.org/organisations/youth/youth-mental-health-first-aid/ (Accessed: 6 November 2025).

MindEd (2025) MindEd: Free educational resources for children’s mental health. Available at: https://www.minded.org.uk/ (Accessed: 6 November 2025).

Ng, E. and Lee, K. (2010) ‘Children’s task performance under stress and non-stress conditions: A test of the processing efficiency theory’, Cognition and Emotion, 24(7), pp. 1229–1238. doi: 10.1080/02699930903172328.

NHS (2023) Anxiety disorders in children. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/children-and-young-adults/advice-for-parents/anxiety-disorders-in-children/ (Accessed: 6 November 2025).

NHS Digital (2023) Mental health of children and young people in England 2023: Trends and characteristics. NHS Digital.

NICE (2023) Guided self-help digital cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for children and young people with mild to moderate symptoms of anxiety or low mood: Early value assessment (EVA4). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/eva4 (Accessed: 6 November 2025).

Rudland, J.R., Golding, C. and Wilkinson, T.J. (2020) ‘The stress paradox: How stress can be good for learning’, Medical Education, 54(1), pp. 40–45.

We Heart CBT (2025) For schools: Resources for schools. Available at: https://weheartcbt.com/for-schools (Accessed: 6 November 2025).

Young Minds (2025) You are not alone. Available at: https://www.youngminds.org.uk/ (Accessed: 6 November 2025).

Caren Smith* is a Content Writer for Learn Science Together, where she combines her passion for writing with her background in health and social care. Holding a Bachelor of Science degree, she brings over 25 years of experience to the table. As a registered nurse and qualified social worker, Caren has worked in learning disabilities and mental health crisis intervention teams. She has addressed complex health needs in paediatric settings and has served as a lead nurse in a boarding school. Caren enjoys sharing her knowledge through various blogs and articles, reflecting her commitment to improving health and wellness.

*Author uses an alias; photo is a representative image