Sleep Smarter, Study Better: The Student Guide to Rest

🕒 Read time: 6 mins

By Millie Vine

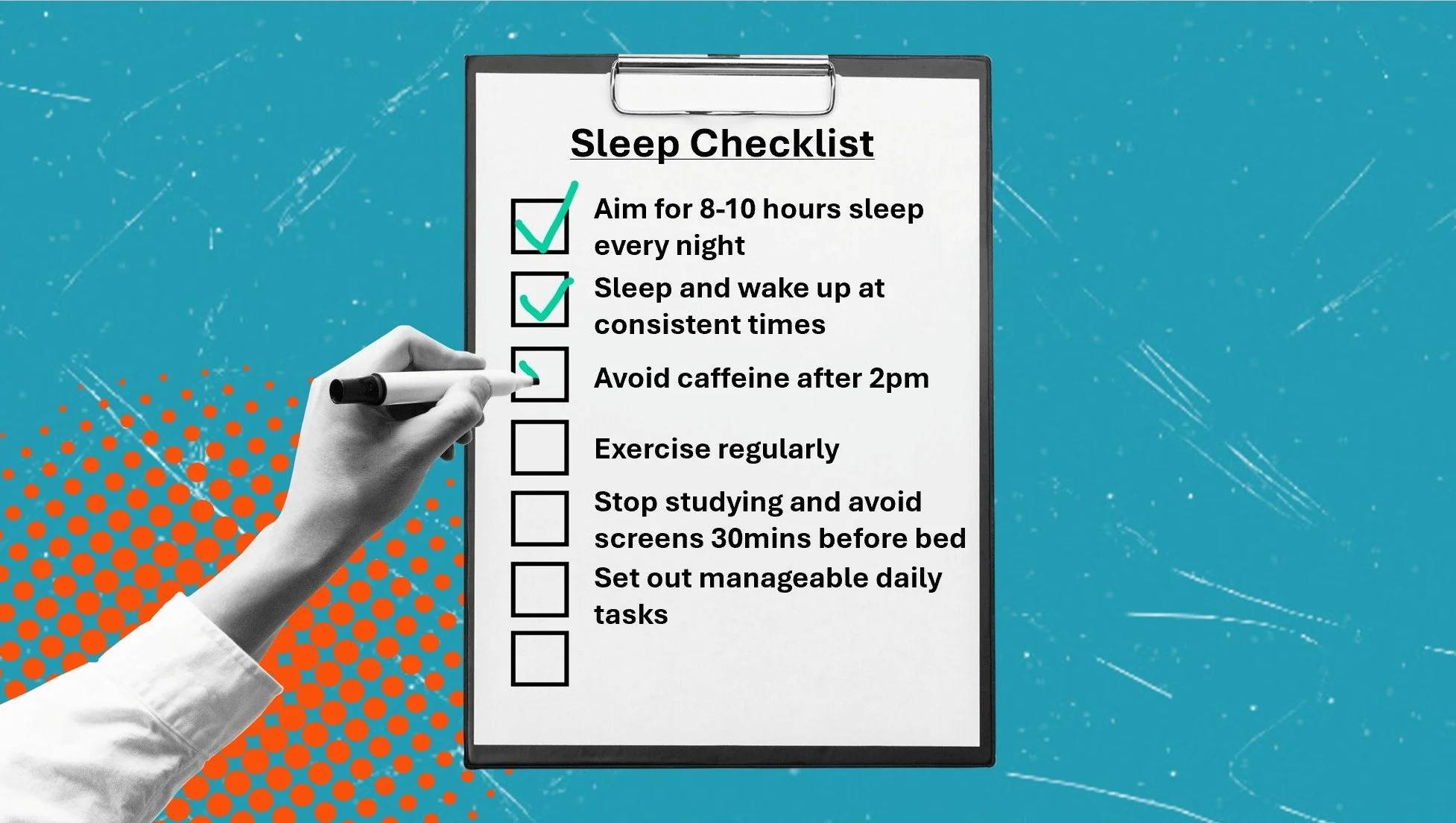

Unsurprisingly, many students spanning from GCSE to University will sacrifice sleep at some point for their studies. But how important is sleep for students? While sleep matters for everyone, students in particular should be prioritising getting 8-10 hours of sleep each night. Adequate sleep has been shown to improve memory, exam performance and overall well-being, all of which are essential for academic success. With the additional pressures of exam stress, deadlines, and busy schedules, it is vital for students to understand the importance of sleep and how to use it to their advantage.

Why Sleep Matters: The Science Made Simple

Memory Consolidation

(Vitelli, 2025)

Sleep has been found to have significant effects on your memory, with clear improvements in the ability to recall facts, events and concepts- known as declarative information (Weighall and Kellar, 2023). The first stage of sleep, non-REM sleep, is important for consolidating the factual information learnt during the day and integrating new and old knowledge together (Niknazar et al., 2015). The second stage of sleep, REM sleep, is closely associated with processing complex declarative information, such as the cardiac cycle, where multiple concepts must be considered together. (Vitelli, 2025)

Due to the sleep stages having different functions in memory, it is essential to obtain enough sleep. When sleep is reduced (or even missed entirely), the brain fails to strengthen communication between neurones which in turn hinders problem-solving skills. Therefore, getting adequate sleep is crucial for students, as it maximises information retention need for academic success.

Cognitive Functioning

(ABLE , 2023)

In addition to a role in memory consolidation, sleep is essential for how the brain functions throughout the day. Students who achieve the recommended amount of sleep are more likely to demonstrate better attention, focus and time management skills, all of which are needed for effective revision. Sleep has also been shown to improve student performance in tasks requiring muscle memory, such as playing a musical instrument or playing sports (Walker, 2008), which can be a great relaxation outlet. This is because sleep allows the brain to clear metabolic waste and rest the regions of your brain responsible for attention and concentration (Benveniste et al., 2017).

Emotional Regulation

During sleep, the regions of your brain responsible for your emotions, such as the amygdala, undergo a reset. REM sleep is particularly important for managing emotions, as the amygdala remains active during this phase, allowing the brain to process feelings in a stress-free environment (Zeidy Muñoz-Torres et al., 2018). Also, the amygdala communicates with the brain’s control centre during sleep, helping to regulate responses to future situations and build resilience to stress. Students who consistently get sufficient sleep demonstrate improved neurotransmitter balance, which is tailored to support learning and performance (Tamaki et al.,2019). This is accompanied by a reduction in stress hormone levels, encouraging a healthier lifestyle and better coping mechanisms during stressful periods.

Physical Health

Beyond the cognitive aspects of being a student, maintaining good physical health is equally important for excelling academically. Sleep has been shown to strengthen the immune system by increasing the production of immune cells, including T-cells and cytokines (Besedovsky et al., 2019). It also helps build the immune system’s memory of pathogens, allowing the body to fight future infections better that could otherwise disrupt learning.

Sleep Like a Pro

1.Establish a Sleep Routine

Evenings can often feel like the only time for catching up with friends or relaxing during busy periods, but without boundaries these activities can destroy a healthy sleep cycle. It was only at university, when my evening schedule was disrupted, did I truly learn the importance of a sleep routine. While I acknowledge that the odd late-night is unavoidable and sometimes the best option to take the mind off work, they should be kept to a minimum. Failing to go to bed and wake up at consistent times due to frequent schedule interruptions is simply not sustainable to succeed for academic or physical success.

(Vecteezy, n.d.)

A helpful strategy to establish a sleep routine is to generate a simple step-by-step guide ending in sleep. This sequence could begin by stopping studying an hour before bed to allow ample time for preparing for the next day. The final 30-minutes before bed could consist of a calming activity such as journaling, reading or stretching. Such routines not only create boundaries between work and rest but also reinforce the body’s internal clock, known as the circadian rhythm.

2. Limit Screentime and Stimulants before Bed

Dzianis Vasilyeu, 2025

Reaching for the phone or an energy drink late in the evening is normalised among students but can be detrimental for the quality of sleep. I will admit that many quick phone checks have turned into hours of ‘doomscrolling’, followed by an unfulfilling night’s sleep. However, reducing the effects of these common influencers has a simple solution: remove them altogether. Perhaps the most difficult suggestion for many students is to leave the phone in another room at least 30 minutes before bed. This is a simple and effective method of eliminating temptation in the time leading up to sleep.

Just as inconsistent routines disrupt sleep, digital devices and caffeine interfere with the body’s melatonin cycle. The blue light produced by mobile phones is thought to be mistaken by the body for natural daylight, suppressing melatonin to maintain the body’s wakefulness (Mortazavi et al., 2018). A study by Sanjeev, Krishnan and Latti (2020) found that those using their phone for more than two hours at bedtime reported significant difficulty falling asleep, shorter sleep duration and greater insufficient sleep.

A growing number of studies report poor sleep quality among young people, caffeine being a notable contributor to the cause. Caffeine plays an interesting role in sleep destruction by effectively shifting the circadian clock back via delaying melatonin release. This is achieved by caffeine binding to the receptors responsible for releasing adenosine, which acts as the trigger for melatonin release (Clark and Landolt, 2017). Therefore, if students are pairing an afternoon ‘pick me up’ coffee with late night scrolling, the body’s natural ability to recognise the need for sleep is impaired, reducing both sleep quality and duration. Avoiding caffeine-containing drinks (tea, coffee or energy drinks), after 2pm is a helpful boundary to set.

3. Plan your Day Time

Cramming work late into the evening can often feel like the only way to keep up with the workload, but it is not without sacrifice. As a typical student, I have found myself being far too optimistic of what can be achieved in a day and trying to tackle beyond my capabilities. So almost without fail, the evening would arrive and I would still be sat at my desk, hopeful that staying up an extra hour later would redeem the day. However, I recognised the detriment this exchange of sleep for work was having on my motivation and quality of learning. So, I looked to make an adjustment to my approach to planning the day to ensure I was managing my expectations and capabilities for a stress-free evening.

While there are endless ways to maximise your daily efforts, an easy adjustment I made was to optimise my daily planning. Prioritising three main tasks each day, such as revising a biology topic or completing math homework, can make the day feel much more manageable with more achievable expectations. Personally, I like to pair this with 60-minute focused study blocks followed by short breaks to help maintain focus on the task at hand. The key is to avoid overloading the workday to make the evenings for winding down to fall asleep, ready for the next day with more energy.

Conclusion

Students should aim for 8-10 hours of sleep each night to optimise their study sessions and overall learning. Sleep plays a crucial role in consolidating knowledge, supporting brain function and regulating emotions during stressful periods. For an improved sleep schedule, establish a consistent routine with a clear end time for studying. Minimise distractions in the final 30 minutes of the day and engaging in calming activities, such as reading, journaling or stretching to prepare the body and mind for a good night’s sleep.

References

ABLE (2023). Examples of cognitive learning theory & how you can use them. [online] ABLE blog: thoughts, learnings and experiences. Available at: https://able.ac/blog/cognitive-learning-theory/.

Benveniste, H., Lee, H. and Volkow, N.D. (2017). The Glymphatic Pathway: Waste Removal from the CNS via Cerebrospinal Fluid Transport. The Neuroscientist, 23(5), pp.454–465. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858417691030.

Besedovsky, L., Lange, T. and Haack, M. (2019). The Sleep-Immune Crosstalk in Health and Disease. Physiological Reviews, [online] 99(3), pp.1325–1380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00010.2018.

Dzianis Vasilyeu (2025). Addiction to internet and chatting concept. Young woman cartoon character lying in bed having rest with turned on smartphone chatting vector illustration. [online] Vecteezy. Available at: https://www.vecteezy.com/vector-art/13708011-addiction-to-internet-and-chatting-concept-young-woman-cartoon-character-lying-in-bed-having-rest-with-turned-on-smartphone-chatting-vector-illustration [Accessed 8 Dec. 2025].

Niknazar, M., Krishnan, G.P., Bazhenov, M. and Mednick, S.C. (2015). Coupling of Thalamocortical Sleep Oscillations Are Important for Memory Consolidation in Humans. PLOS ONE, 10(12), p.e0144720. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144720.

Okano, K., Kaczmarzyk, J.R., Dave, N., Gabrieli, J.D.E. and Grossman, J.C. (2019). Sleep quality, duration, and consistency are associated with better academic performance in college students. npj Science of Learning, [online] 4(16). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-019-0055-z.

Tamaki, M., Wang, Z., Barnes-Diana, T., Berard, A.V., Walsh, E., Watanabe, T. and Sasaki, Y. (2019). Opponent neurochemical and functional processing in NREM and REM sleep in visual learning. bioRxiv . doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/738666.

Vecteezy (n.d.). People exercise and fitness cartoon set. [online] Vecteezy. Available at: https://www.vecteezy.com/vector-art/693406-people-exercise-and-fitness-cartoon-set.

Vitelli , R. (2025). Stages of Sleep: What Does Each Stage Do? (Winter 2024). [online] TalkAboutSleep. Available at: https://www.talkaboutsleep.com/stages-of-sleep/ [Accessed 7 Dec. 2025].

Walker, M.P. (2008). Cognitive consequences of sleep and sleep loss. Sleep Medicine, [online] 9(1), pp.S29–S34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s1389-9457(08)70014-5.

Weighall, A. and Kellar, I. (2023). Sleep and memory consolidation in healthy, neurotypical children, and adults: a summary of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Emerging Topics in Life Sciences, 7(5), pp.513–524. doi:https://doi.org/10.1042/etls20230110.

Zeidy Muñoz-Torres, Velasco, F., Velasco, A.L., Río-Portilla, Y.D. and María Corsi-Cabrera (2018). Electrical activity of the human amygdala during all-night sleep and wakefulness. Clinical Neurophysiology, 129(10), pp.2118–2126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2018.07.010.

Millie is a Tutor and Content Writer for Learn Science Together, currently studying an Integrated Master’s in Neuroscience. She achieved an A in A Level Biology and grade 9s in GCSE Mathematics and Physics. Millie tutors Mathematics up to GCSE and Biology up to A Level, focusing on clear subject understanding and strong exam technique in a supportive learning environment.